Posts Tagged ‘bereavement’

Jessica’s Reflections as an Adult Grieving Child

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

November is considered Bereavement Awareness Month, and this year November 16 commemorates Children’s Grief Awareness Day. 1 in 14 children in Canada will experience the death of a parent or sibling by age 18.

The first funeral I attended was at the age of 7 when my Nana, or paternal grandmother died. My family buried my maternal grandfather 7 years later after he experienced a stroke when I was 14 and my mother was still in treatment for cancer. 13 months later, I would be burying my mom at age 15 after dying of cancer. She was 49. We would be gathering again less than two months later to bury my godmother and aunt who died suddenly and unexpectedly. Every time I felt like I had found footing on the shores of my grief, another loss would crash over me like a wave, dragging me out to a sea of unknown.

Navigating puberty can be an exciting and challenging transition in our life that also can have us feeling grief from non-death losses as we figure out who we are becoming. Not only was I trying to make sense of hormones and changes during this time of life, but my mom – the person who I would have gone to for support was no longer a phone call or hug away. Parents or trusted adults are people children often turn to for support, but my circle of trusted adults was shrinking. My peers were focused on what to wear on civvies day (a day where we didn’t have to wear a uniform), while I was focused on just surviving.

I felt so alone in my grief, although my twin, younger brother, dad, and other relatives in my life were also grieving. Friends would try to show up for me, sometimes it didn’t land well. There are friends who had never been to a funeral that walked with me in the depths of my grief who still hold a special place in my heart and life. I felt like I was in a sea of students in the hall between class with a flashing neon sign that read “Human with all the dead people in their life”. At times I could tell how awkward both peers and adults in my life were when approaching me – what do you tell someone when you’ve never experienced a death? And the person who is grieving can’t even legally drive a car!

There was no right or wrong way for me to grieve, but I had to find my own way to grieve. Sometimes they were helpful, and other times the things I did I thought helped me with my grief were not so helpful.

I am fortunate that despite the not-so-careful caring people in my life that made me feel invalidated, I had many caring adults in my life who let me know that grief is natural, and let me share stories of my loved ones. Within the first year of our loss, each of my siblings, my father, and I attended a grief support group. Walking into my first group was both scary and exciting: other teens like me?! The peer volunteer who co-ran these groups was actually someone I knew personally, but had no idea that they had been touched by death too.

I felt deep sadness, guilt, and anger in that group. I also felt deep connection, joy, and even laughter. We got to talk about our sibling, parent, or other close person in our life we were grieving. Talking about grief didn’t make me feel more alone, or worse, it made me feel LESS alone. That we all grieve what we are connected to. That’s it’s okay to not be okay. That sharing our stories of our person and our pain can be healing when we have the right kind of listener in our corner. And that we never have to walk alone at any age or stage of our grief.

Ripples of Grief: Supporting Ourselves, Others, and our Communities After a Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

When death knocks on the door of a community, each of us are impacted. Sometimes a death will touch many lives across a community, whether people knew the deceased personally or not. We may grieve the death of a family member, friend, or acquaintance, a well-known community member, or someone we are linked to by age, location, circumstances, etc. Community grief can feel overwhelming – we must tend to our own grief, but others in our life are grieving and hurting too. Each person in a community will grieve differently depending on their relationship to the person who has died, their own prior experiences of loss, and the unique coping strategies they rely on in grief.

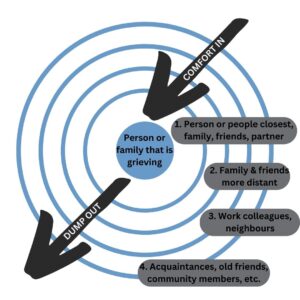

Developed by psychologist Susan Silk and Barry Goldman following Susan’s experience with a health crisis and her diagnosis with breast cancer, Ring Theory helps us learn how to support others and ourselves when a community death occurs.

Like a ripple on water when we drop a pebble into it, imagine a series of concentric circles. Those directly impacted by the crisis or death are in the innermost ring, with each outer ring consisting of those further removed from the crisis or death. Generally the immediate family, or those who lived with the deceased,are in the innermost ring, with close friends and other family in the next ring, co-workers and acquaintances in the next ring, and those in our greater community in the outer rings.

When someone experiences a death, those in outer rings pour comfort in, while those in inner rings are allowed to “dump” their thoughts or feelings out. When someone in an inner ring is dumping out their feelings, those in outer rings can show up with acceptance and care, listening and validating the person’s experiences.

Pouring comfort in can also be the offer of specific, practical help. This approach seeks the griever’s consent to accept specific support and comfort, it lets the griever say yes or no to the offer, and can confirm what kinds of support are most helpful to them. It’s important to offer support on the griever’s terms.

When a community faces loss, many who are impacted want to share their feelings about the loss. Susan recalled during her cancer treatment how some folks she did not have very close relationships with in her community would show up unannounced, forcing her to accept support, or people would talk about their own feelings about her diagnosis. Dumping feelings onto someone in an inner circle is not helpful. It can leave those experiencing the loss most personally as if their loss is unacknowledged. When we know which ring we sit in after a death, we can connect to our own outer rings anytime we need to tend to our feelings of grief. If we find ourselves thinking about reaching out for support from someone who is in an inner circle compared to our relationship to the deceased, we should take a step back. Is there someone else that may be located in the same ring as us, or someone in a ring outside of us that we can reach out to instead? Sometimes actually drawing out the rings of folks in our own life impacted by a death can clarify where we need to support others, and who we can connect with for our own support.

Whether supporting others, or seeking support ourselves, a helpful phrase may be “Would you like to be heard, helped, or hugged?” Being heard means receiving supportive listening and validation. Being helped may mean brainstorming and collaborative problem-solving, or providing specific practical help with tasks. Sometimes there are no words or help we can offer, but, if welcome, our steady presence and a comforting hug can communicate our support.

Each person in a community will be impacted differently by a community death. It’s important to remember this theory about who we need to pour comfort into, and who we ourselves can dump out to as we navigate a community loss.

Articles Reviewed for Blog Post:

https://karenwulfson.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/How-not-to-say-the-wrong-thing1.pdf

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-xpm-2013-apr-07-la-oe-0407-silk-ring-theory-20130407-story.html (actual article in LA Times first written by Susan Silk – first link is PDF version of same article)

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201705/ring-theory-helps-us-bring-comfort-in

Saved by a Unicorn: How I Found the Positive in Grief, One Stitch at a Time

By Cee Fisher

I’ve tried many ways of handling grief. I love the challenge of redirecting the negative energy derived from grief, turning it into something positive and useful. Of course, things don’t always go as planned. Still, it feels good to know I have the power to switch things up and try to create more of a sustainable balance in my life. It gives me a sense of control and helps me to feel more hopeful.

One of my most devastating experiences with grief was when I found out my soulmate, Reuben, died. He was the rarest, most caring soul I’d ever met. People respected him. They listened to him. Reuben and I were engaged for a couple of years, and although our breakup was complicated there are a few facts you should know. When we last spoke, we were living in separate countries. He was living on kidney dialysis. I was raising our son alone. They had never met. We were making plans of reuniting. Somewhere along the line, our phone numbers changed and caused us to lose touch. I searched for him for ten years. When he died, a letter that he had written to me was discovered in his belongings. In the letter, he said he needed to speak to me as soon as possible. We never got to have that conversation, and he never got to meet his son.

Googling his name had become very routine, but this time was different. A link appeared. My jaw dropped excitedly until I followed the link and saw the word “late” typed next to his name. That was it for me. That was when my world came crashing down. It felt as if I was violently kicked off cloud 9 and slammed in the gut with a sledgehammer. I opened my mouth and felt my soul wailing, but it was as if I were crying in reverse. I could not breathe. I truly believe that was the day I gained full understanding of what a meltdown feels like.

I hid in my room for about a week, curled up in fetus position, aimlessly crying out Reuben’s name. I felt totally lost and defeated, and knew I needed something else to focus on. Life had taught me that. I needed to engage in something therapeutic, and washing dishes was definitely out of the question. I decided to buy a crochet hook. I crocheted every day, and soon began receiving requests for paid orders. I began selling at outdoor events, surrounded by nature. In no time, I was designing and crocheting custom-made items, including a unicorn my neighbor ordered for her daughter.

Looking back, I had no idea how to even continue to live. A simple attempt at something therapeutic sent the negative bereavement energy into a positive direction. It made me realize my strengths, at a time when I felt I had none at all. It provided a space where I am now better able to manage grief when it hits.

Alongside

By Mike Bonikowsky

Grief is the great leveller, and the great divider. Everyone grieves, sooner or later, but no two people will experience it in the same way. No two bereavements are the same, and neither are any two consolations.

This is only more poignantly the case for people with developmental disabilities. Not only is their grief completely unique, but they are often unable to express it in traditional ways. How are we to support someone through the grieving process when they cannot, or will not, tell us what they are thinking and feeling about their loss? The answer is simple, and difficult.

In Christian theology, there is a concept called “the Holy Spirit”. This is the invisible piece of God that is everywhere all the time, with and within all people. The name given to this in the original ancient Greek is the “Paraclete”, literally, “The one who comes alongside.”

That is also our best, and only role, when supporting a person with a developmental disability to grieve. We must be the one that comes alongside. There is no closer place we can get to. We must be present, be with, perhaps not understanding or comprehending what the person we support is experiencing, but alongside them nonetheless. We must be there, ready to provide whatever we can discover of their unique need in grief.

But that coming alongside must begin before the bereavement. We must already have been there through the happier seasons of the person’s life, if we are to know them well enough to read the language of their grieving, and hope to know in what little ways we may support them. Supporting a person with a developmental disability to grieve is not a matter of coming alongside, but of remaining where we already were. It is a matter of knowing and being known by them, of being trusted. It is not so much a matter of doing anything for the person, but of being something for them: A safe place, a consistent and reliable presence. It is to be a fixed point in a confusing, chaotic world, someone of whom they can say: “When that person is here, I can expect things to be like this.” Only when this relationship is present and well-established in the ordinary times can we come alongside in the darkest, loneliest season on the person’s life, and hope to meet their unspoken needs.

And usually the answer to those needs is what it has always been: To simply be there with them, to prepare a meal for them and do the dishes afterward, to help them wash body and find clean clothes to wear. To open the curtains in the morning, so that when they emerge from the dark cave of their unique grief, for however short a time, they are greeted by a world that has not ended, and a face that they know, and that knows them.

Grief and Disability: Carrie’s Story

By Carrie Batt, Grief Educator

My son says I am a mover and a shaker. He tells his friends that because of my extensive travels abroad and my volunteering. When his friends ask: “Why did she do that?” he always tells them “Because my mom believes that ‘anything is possible’.” As I look back on my journey, I know where I picked up this motto. When my baby brother was born, the doctors told my parents: “he will not walk, talk, nor know who you are”. From that day on my parents embodied that motto ‘anything is possible’ and in the end my brother does far more than walk and talk. This circumstance introduced me to the disability community knowing that people with disabilities deserve and can do more. Interestingly, I have had the privilege of working within the developmental sector in a variety of positions for more than thirty years.

In 2018, I added to my parents’ motto ‘anything is possible’ and included ‘everyone is worth it’. I added those words to the motto right after I had attended a kintsugi workshop offered by Rami Shami, a prominent member within the deathcare community. As soon as I realized that Rami had spent the last 30 years caring for the dying. I inquired about his experience in death, dying and disability. Rami unfortunately, had no experience in supporting people with a disability who were dying. Upon learning about the sheer lack of support and expertise on this topic, I proceeded to complete the end-of-life training with Beyond Yonder Community Deathcare program. Soon after, SEOL Care was created, which offers a disability-sensitive approach to death, dying, and disability.

It has become clear to me over time that we have much work to do to ensure the delivery of disability-sensitive grief literacy and grief support. In March of 2022 my proposal for four 1-hour sessions was approved, we provided the program for 20 participants. My heart was full in each session.

My heart remains full of hope that conversations, education, and expertise about disability sensitive end of life care and grief support will gain momentum as more and more people join in on this vital conversation.

Currently, there are several rays of hope that suggest grief education and support can and will be offered in a more inclusive way. As a certified grief educator, I now offer online disability-sensitive grief support services for individuals and groups. My employer is offering disability-sensitive grief literacy sessions. The Bereavement Ontario Network has shared information through their newsletter and in a network webinar, where the gentleman I support and I were the guest speakers. Bereaved Families of Ontario have been receiving multiple requests to provide grief resources for the neurodivergent community. Additionally, Bereaved Families of Ontario are seeking out speakers with lived experience related to grief and under-represented communities for their grief literacy series. I remain grateful knowing that these are hopeful times, and these examples are a positive step in the right direction.