Posts Tagged ‘community grief’

Community Grief Toolkit [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in the community. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and how to build the resources for further support.

Calls to Care, Calls to Action: Bearing Witness to Global Catastrophic Loss of Life and Traumatic Events

By Jessica Milette, MSW/RSW

Human beings are wired for connection. Many of life’s most difficult experiences leave us feeling isolated, and connection can be a healing path. Currently, many of us are watching intense acts of genocide and death occurring internationally literally at our fingertips.

Why are our hearts tearing open at the witnessing of this pain? Why do we feel so helpless while we bear witness to pain and loss on massive levels that we may not feel entitled to experience because we are not directly impacted by these events?

In the words of a Jewish text, the Pirkei Avot “Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.” And currently, there is so much grief in the world. Coming together in grief can be healing and a call for action to demand change in the face of oppression and genocide.

We bear witness to stories of mass loss of lives, stories of families in Gaza being forced from their land, loss of culture and traditions, and countless other ways systems of colonization and oppression can contribute to other non-death losses those who are directly affected currently and have historically faced. As we discussed in a previous article, we can also experience collective grief following natural disasters, accidents, international conflict, and acts of violence that have resulted in catastrophic loss of lives.

Loss also recognizes loss: hearing about international events that have resulted in the loss of lives, may have us thinking about our own losses in our lives. Depending on where we were born, the identities we hold, and how we move through our society can also impact our experiences of loss. We may be experiencing fear not knowing someone we love is alive who lives in an affected area. We may have experienced diaspora, and our communities in our home country are victims of violence. We can also feel grief deeply if we do not have a direct connection through our identities to those more directly impacted by the loss. Human beings are wired for connection and empathy – we hurt when we see hurt.

Some calls to care for when we experience collective grief:

– Being mindful of how much content you are consuming. It’s okay to step back or limit the types of information we choose to process. Perhaps reading articles from those who are directly impacted by these events feels more accessible than watching video coverage which can be graphic.

– Tend to your heart and body: the experience of grief can be demanding on our minds and bodies. Take time to rest, hydrate, and nourish yourself in healing ways. Caring for ourselves gives us more capacity to provide care to others we are in community with.

– Acknowledge your feelings. You may be feeling deep grief, despair, anger. It may feel easier to shut down these feelings, turn off our news feeds and burrow into our covers. But it is important that we give ourselves permission to feel and express our collective grief.

– Remember, POUR IN and DUMP OUT. Pour in support to those in your life who may be more directly impacted by these losses. Dump out your own grief to those who are not as directly impacted compared to your own positionality to these events.

– Grief AND joy can coexist. We can hold space to process our feelings of grief while also remaining open to experiences of lightness and joy.

– Share and express your feelings of grief with a supportive other. What types of support are most helpful to you when you have experienced grief?

There is power and healing in community. Collective action in moments of collective grief history have exposed injustice, and demanded action. We may also feel fatigued by the sheer volume of loss we are witnessing. When we feel fatigued, it can be easy to turn away and tell ourselves “this isn’t about me”. Turning away from these moments in history actually further silences those who are facing oppression, marginalization, and loss on a grand scale. Collective grief invites us an opportunity to gather collectively as a community to offer support, heal, and advocate.

Engage how you can. Everyone’s capacities will be different, and each of these things can help change our perspectives or ask for change:

– Learning and UnLearning about the topic

– Gathering in community through teach-ins, demonstrations, community vigils, or protests

– Create space for joy as we call for action. Could you host a movie night where you and supportive others write to local governmental representatives? Have a craft night to make signs for a local demonstration.

– Reflecting on our own experiences from a lens of critical self-reflexivity.

– Holding space for difficult conversations with loved ones

– Being critical as we read information – whose story is being centered, where is this source from

– How could I use the privilege(s) I have to amplify marginalized voices in this space?

Unlearning is uncomfortable. It asks us to sit and critically examine how our identities shape our view of the world. Taking stock of how your privileges or silence may have made you complicit in moments of oppression and marginalization. It may challenge your entire worldview. These things are uncomfortable. Discomfort is not a “bad” feeling – it is something that is uncomfortable to sit with. But sitting with our discomfort and increasing our tolerance to hold these uncomfortable feelings as we unlearn is part of this work. And it is so needed. We all have gifts of the head, heart, and hands we can lean on in times of collective grief, and in times we demand collective change.

What Can Help with Early Traumatic Grief?

By Claire Irwin

When your child dies you are thrown into a nightmare. None of this is expected to be easy.

Even after several months, it still isn’t. There have been some things that have helped us during

our grief. Maybe they will help you, too.

1. Let someone organize a meal train. The community rallied, making sure we had meals

delivered to our home for weeks after our daughter died. I have zero idea what we would have

done without this. Right after this traumatic loss I couldn’t even think about eating, let alone

cooking and meal planning.

2. Grief counselling. Our counsellor comes every week since the second day. Some may not agree, but honestly, we have learned some great survival tools and have our feelings validated.

To be able to talk about it all in a safe environment is very helpful, and just talking about

everything helps.

3. Find something to keep you busy. Mind you, we haven’t found our way to any gym yet or back to work, but we find other ways to move our bodies. Gardening, cutting grass, walks,

landscaping, anything really to get our bodies moving has really helped us.

4. Try journaling. I wish I started this earlier. If you can find it in you to do it, I recommend it. For me personally, it helps get whatever is in my head out on paper. I document how I’m feeling. I also get my anger out on paper too. I’ve been learning that you can let it build up inside of you. This energy needs to get out. I find writing very helpful for me. I journal daily. Plus, it helps me keep my days in order because they tend to blend.

5. Let your support system hold you. This has been a huge help. I don’t know where I would be today if I didn’t have the people closest to us. Lean into them and let them help. Use them as sounding boards. Whatever it is you need, if they are willing and able to be there for you, let

them. It’s not easy asking for help or accepting it, but it’s helped us feel loved and seen. It’s also

helped us back on our feet a bit.

At the core of it all, just remembering to breathe is sometimes all you can do. Something our

grief counsellor has taught us right from the very beginning:

Inhale 4 seconds…Hold 7 seconds…Exhale 8 seconds. Repeat as needed.

Like I said, surviving this grief and trauma isn’t easy, and it doesn’t come with a handbook. We

are all just doing the best we can, and it’s sucks all at the same time. Our loss cannot be fixed, it

can only be carried, and these are some of the things helping us to carry it now.

Thoughts on International Overdose Awareness Day 2023

By Jessica Milette, MSW/RSW

August 31 is International Overdose Awareness Day, a day where we honour and remember those who have died by drug poisoning.

We lead multifaceted lives, and the deaths of those we love who have died by drug poisoning contain multitudes. The death of a loved one can bring intense grief, shock, anger, shame, or guilt. People who use drugs, and those who love them that they leave behind, face stigma in North America’s dominant, settler culture.

It is this stigma of drug poisoning deaths, the othering of another’s valid grief, that places a barrier to one of the greatest things we can offer to ourselves and each other: connection. Those who have died by drug poisoning are parents, children, siblings, aunts, and friends. Those who welcomed us with open arms for an embrace, those who worked alongside us, and those who have faced much suffering and marginalization.

Grief can be an isolating experience; having opportunities to heal in community and share the stories of those we love who have died are so important. It is never about HOW they died, but WHO they are. Saying their name out loud, listening to their favourite music, and sharing stories of joy can help. Sometimes we need to share our stories of frustration, guilt, or sorrow with others who have experienced the death of a loved one.

We don’t have to be impacted by the death of a loved one by drug poisoning to support others in our community who are in pain. Grief and the losses we face cannot be fixed. We can feel helpless in the face of seeing someone we care about in the depths of grief. One of the biggest things we can do as supporters is to not shy away from grief – those grieving can feel supported when others ask them about their person or use their name in conversations. Sometimes telling grievers to “call me if you need anything” can feel overwhelming. By offering specific, practical support like mowing their lawn or dropping off groceries gives grievers a choice. If they do not accept the support you offer, be open to listening to what support they do need as what you may have found helpful might not be the type of support they need. A helpful phrase I’ve used to communicate to people in my life when I need some grief support, or when I’ve offered support to those in my life grieving has been: “Would you like help (with a task or to brainstorm), would you like to be heard (where I will sit and listen without judgment and sit with you in your grief), or would you like a hug (sometimes we need a hug through a tough moment)?”

In addition to these personal losses, we also face these losses as a community. State of Emergencies declared by public health authorities due to the drug poisoning crisis are more common than they were before. The Canadian Healthcare system is still reeling from a pandemic and is unable to meet the current demands to address this health crisis. Drug poisoning deaths are highest for those in our community that face high levels of marginalization, oppression, and stigma despite human beings’ universal needs for safety, connection, community, and care..

People who use drugs, like all human beings living on Stolen Land on Turtle Island deserve access to care, community, connection, and safety in all areas of their wellbeing. Harm Reduction is an important but often underappreciated pillar in Canada’s healthcare system that offers safety, community, compassion, and care while keeping the dignity of the person who uses drugs at the heart of this work. Harm Reduction workers create community for those who may feel isolated or have been excluded from other communities they belong to due to their drug use. They provide spaces for people to learn new ways to be in relationship with drugs, how to be safe when using drugs, and getting connected to other supports for their whole health. Not all drug use is inherently problematic, and harm reduction support can look like many things: from helping those wishing to be abstinent from drug use to helping those who are still using drugs to use them in safer ways.

Just like we come in community to honour those who have died, through community we can continue to hold systems accountable and advocate for equity, justice, safety and health for all.

Ripples of Grief: Supporting Ourselves, Others, and our Communities After a Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

When death knocks on the door of a community, each of us are impacted. Sometimes a death will touch many lives across a community, whether people knew the deceased personally or not. We may grieve the death of a family member, friend, or acquaintance, a well-known community member, or someone we are linked to by age, location, circumstances, etc. Community grief can feel overwhelming – we must tend to our own grief, but others in our life are grieving and hurting too. Each person in a community will grieve differently depending on their relationship to the person who has died, their own prior experiences of loss, and the unique coping strategies they rely on in grief.

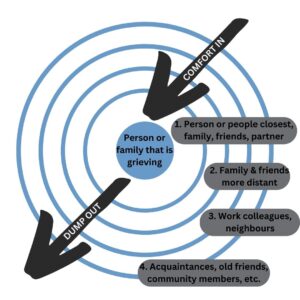

Developed by psychologist Susan Silk and Barry Goldman following Susan’s experience with a health crisis and her diagnosis with breast cancer, Ring Theory helps us learn how to support others and ourselves when a community death occurs.

Like a ripple on water when we drop a pebble into it, imagine a series of concentric circles. Those directly impacted by the crisis or death are in the innermost ring, with each outer ring consisting of those further removed from the crisis or death. Generally the immediate family, or those who lived with the deceased,are in the innermost ring, with close friends and other family in the next ring, co-workers and acquaintances in the next ring, and those in our greater community in the outer rings.

When someone experiences a death, those in outer rings pour comfort in, while those in inner rings are allowed to “dump” their thoughts or feelings out. When someone in an inner ring is dumping out their feelings, those in outer rings can show up with acceptance and care, listening and validating the person’s experiences.

Pouring comfort in can also be the offer of specific, practical help. This approach seeks the griever’s consent to accept specific support and comfort, it lets the griever say yes or no to the offer, and can confirm what kinds of support are most helpful to them. It’s important to offer support on the griever’s terms.

When a community faces loss, many who are impacted want to share their feelings about the loss. Susan recalled during her cancer treatment how some folks she did not have very close relationships with in her community would show up unannounced, forcing her to accept support, or people would talk about their own feelings about her diagnosis. Dumping feelings onto someone in an inner circle is not helpful. It can leave those experiencing the loss most personally as if their loss is unacknowledged. When we know which ring we sit in after a death, we can connect to our own outer rings anytime we need to tend to our feelings of grief. If we find ourselves thinking about reaching out for support from someone who is in an inner circle compared to our relationship to the deceased, we should take a step back. Is there someone else that may be located in the same ring as us, or someone in a ring outside of us that we can reach out to instead? Sometimes actually drawing out the rings of folks in our own life impacted by a death can clarify where we need to support others, and who we can connect with for our own support.

Whether supporting others, or seeking support ourselves, a helpful phrase may be “Would you like to be heard, helped, or hugged?” Being heard means receiving supportive listening and validation. Being helped may mean brainstorming and collaborative problem-solving, or providing specific practical help with tasks. Sometimes there are no words or help we can offer, but, if welcome, our steady presence and a comforting hug can communicate our support.

Each person in a community will be impacted differently by a community death. It’s important to remember this theory about who we need to pour comfort into, and who we ourselves can dump out to as we navigate a community loss.

Articles Reviewed for Blog Post:

https://karenwulfson.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/How-not-to-say-the-wrong-thing1.pdf

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-xpm-2013-apr-07-la-oe-0407-silk-ring-theory-20130407-story.html (actual article in LA Times first written by Susan Silk – first link is PDF version of same article)

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201705/ring-theory-helps-us-bring-comfort-in

Jim – Grief and policing

Jim – Grief and policing

Jim – ” I believe that policing is a profession that is constantly filled with loss. Whether it is losing a partner, a friend, or a loved one, police officers are always dealing with the pain of loss. I also talk about my own personal experience with grief, and how I have learned to cope with it. I hope that this video will help other police officers who are struggling with grief.”

Jim – Police culture and grief

Jim – Police culture and grief

Jim talks about how grief is a natural part of life, but it can be especially difficult to deal with when you’re in the police culture. There’s a lot of pressure to bottle up your emotions and not show weakness, but that’s not healthy. It’s important to find healthy ways to cope with your grief, whether it’s talking to a therapist, joining a support group, or simply spending time with loved ones. You’re not alone, and there are people who care about you and want to help.

Kristal – The Value of all Those Lost

Kristal – The Value of all Those Lost

Kristal emphasizes that the lives of those lost to drug poisoning had value, they were an opportunity that was lost, and that the community is missing so much in their absence.

Kristal – Drug Poisoning During Pandemic Stigma

Kristal – Drug Poisoning During Pandemic Stigma

Kristal discusses how the pandemic has created additional stigma surrounding those who use drugs. She discusses how it seems like some losses are treated as more deserving of being mourned than others. Many people have had to grieve privately instead of publically within a community. She touches on the state of the public health system during the pandemic.

A Million Other Things: Grieving a Drug Poisoning Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

A parent sits across from me, anxiously wringing their hands. They will be returning to work after the sudden death of their child. “What if they ask? Do I tell them that they died of an overdose?” Terror flashes across their face. “What if they judge me? My child? What if they think I’m a terrible parent?” We take a moment to reflect on their child and I ask them to tell me about them. They pause, but then I notice their hands aren’t as tense as they cross them over their shoulders. “They were so thoughtful and gave the best hugs. Their smile would light up any room.”

Sister, father, son, niece, best friend – some of these words might be how you would describe your loved one who has died of an overdose or drug poisoning. People Who Use Drugs (PWUD) are not defined by their substance use – they are a million other things to those who love and miss them dearly. Drug poisoning and overdose deaths are stigmatized in our society. The focus is on how the person died, not who they are. Society still holds onto old notions and beliefs about drugs which come with a value judgment about people who use drugs, which further contributes to stigma. Not everyone who uses drugs is an addict and not all drug use is inherently problematic. People who use drugs deserve dignity and respect when we are remembering and honouring those who have died by overdose or drug poisoning.

More stigma means less support for people using drugs and those that support them. Much work has been done and continues to be done to dispel myths and stigma about addiction, drug use, and those who use drugs. Addiction is an illness: something that someone lives with, not something that defines them. These same values and judgments society has about drug use aren’t attached to folks who die of other illnesses. Society tends to view drug use and those who use them as a black and white issue. However, those who love someone who uses drugs weave a rich, colourful tapestry made of stories, reminders, and feelings about their loved one.

In my years as a grief therapist, those left behind want to share a special moment or memory about their loved one with a trusted other. When one is grieving a drug-poisoning death, this trust and sacredness without judgment offers the freedom to sit in the entirety of their grief—the grief they felt when their loved one was alive and when they died. Taking the time to use a loved one’s name in conversation, and asking the griever to share something about their loved one is a powerful tool for us on our grief journey. By initiating these types of conversations, we let the griever know that if they wish to, they can talk about their loved one. Sharing our stories are some of the most powerful ways one finds connection and healing through grief. It helps us feel less alone in our grief by sharing about what makes our person special. Those we love and grieve aren’t just a person who uses drugs – they are so much more. May each of us continue to share stories about our loved ones and the many facets their lives hold.

*DISCLAIMER* The scenario described in the article is a general reflection upon themes the author has witnessed through their grief counselling work and does not represent a specific individual in order to protect the confidentiality of service users.

Nicole – Stigma Surrounding Drug Use

Nicole – Stigma Surrounding Drug Use

Nicole discusses how the stigma around drug use has an impact on how people feel able to grieve when those in their community are lost.

Nicole – Pandemic’s Effect on Grieving as a Community

Nicole – Pandemic’s Effect on Grieving as a Community

Nicole discusses the ways the pandemic has affected the way people grieve as a community.