Posts Tagged ‘Loss’

Who are we to Decide? The Many Paths through Grief

A lot of my work with clients involves hearing their stories, but also answering many questions about if their grief is “normal”. Their grief is overwhelming, and our dominant culture’s strong message is – that grief should be kept at its edges, I often find this pervasive intention creeps into griever’s experiences – and my worldview at times. I even catch myself apologizing for crying in public spaces, shutting down my process. There are many ways of doing, being, and knowing, which I continue to learn through the spaces I hold with others.

A Ghanaian woman living in Canada shared with me her experiences after the death of her mother who died in their home country of Ghana. Traditionally, when someone dies in their community, their body is laid in the home and the entire community is welcomed. Feasts, songs, stories, cries, wails. Their world stops – and for longer than a mere few hours. Loud, open expressions of grief are honoured and welcomed.

A Chinese woman expressed worry that something was wrong with them. After attending a grief support group, she felt worse rather than better. So many people have shared how helpful these spaces had been for them, but this wasn’t her experience at all.

A White man sits across from me and tells me his wife encouraged him to try therapy because “he isn’t grieving” since he doesn’t openly share his emotions. One finds comfort in storytelling, talking about the loss of their child, and finds crying cathartic. He speaks about the qualities and memories of their child, practical matters over emotional ones, and their passion for bringing forth advocacy and change concerning the drug poisoning epidemic.

An Indigenous woman speaks about a ritual in their community where the grieving family cuts their hair after a loved one’s death. On one hand, they feel guilt at times for not engaging with it because it “makes it real”. However, getting a tattoo of a flower they got after their mother’s death was their ritual.

In North America, we are quick to try to “fix” or “solve” grief. There are many books, support groups, and online communities about grief. Yet I have had more than a handful of clients who have recently experienced a death share how their doctor offered them a psychopharmacological medication before their doctor may even acknowledge their loss. I think about the Ghanaian woman, and how open and welcome grief is within their local community. I can only imagine how stifling tending to these rituals in North America may have felt to this person if their mother died in Canada.

There is no “magic pill” to prescribe, but I know many people in the depths of their grief wish there were something, anything to “fast forward” through the sleepless nights, waves of emotion, and grief bursts to a place where their grief feels less overwhelming. There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

Here are some gentle prompts for you to explore some ways to tend to your grief:

What brings meaning or comfort, to you?

Are there particular rituals your community (spiritual, ethnic, other identities) find important to help honour your loved one?

Which rituals do you find comforting but at times find it difficult to share with others?

Just because White colonizer culture is dominant in North America, does not mean those perspectives are “the right way” through grief and loss. There are many ways of being, doing and knowing in life and in grief.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Holding Space for The Many Faces of Grief on Father’s Day

A lot of blog posts and articles about grief and special days tend to focus on how to navigate these moments when our loved one has died. Often these articles of grief also talk about the ways we have deeply loved or cared for the person who has died.

Grief is a natural response to when we lose someone or something we have had a connection to. So what happens for the grievers who have had a not-so-loving relationship with the person who has died, or has experienced an estrangement?

I’ve heard folx sitting across from me talk about how surprising it was to experience a surge of emotions after finding out their father died after being estranged for half their life. Another person talked about how frustrating it was to hear others ask them why it didn’t seem they were grieving, and that they “should” be more tearful because their father had died, however, these people did not know how difficult their relationship with and to their father was when he was alive. Someone else shares how hard it is to carry the grief of deciding to estrange themselves from their father.

To those of you grieving and/or approaching this Father’s Day with complex feelings and memories of a not-so-loving relationship: you are not alone. We grieve because we have had a connection – and a connection can be filled with many things. Love may be part of these connections in our life, but so many other complex emotions, and situations can be part of these connections. People are complicated. Love is complicated. Grief is also complicated.

We can grieve that we did not have the relationship with the person we needed, grieve the parts of the person we miss, or even grieve for a future where perhaps we may have been able to repair the rupture in our relationship.

Grief can feel even more complicated when we have a complex relationship with the person we are grieving. It can make us feel even more isolated. Disenfranchised Grief is any type of grief where society has denied the griever’s right, role, or capacity to grieve. When a relationship has been not-so-loving we may hear well-intentioned people telling us ‘You shouldn’t feel grief because X was not a good person or not a big part of your life’. Our society also tends to prioritize grief experiences through death, and not non-death losses like an estrangement from a parent.

Whether your father has died and you had a complex relationship with them, are grieving the living relationship with your father you never were able to have, or grieving an estrangement from your Father your feelings are valid. Grief is not just one emotion, but is a natural response that can have many different emotions depending on the person. It’s okay if you feel anger, frustration, regret, guilt, and even relief. Special days where all we hear and see are advertisements talking about Father’s Day can bring up extra waves of grief as we near this date.

Here are some gentle reminders if you are moving through Father’s Day this year and have a complicated relationship with your father, or paternal figure in your life:

- Give yourself permission to write a letter to this person, expressing the things you never have been able to say. It can be a place to put down all those thoughts and feelings that you can then release. Feel free to rip this letter up into a tiny pieces, flush it down the toilet, or even safely burn the page.

- Spend time that day however you need to and with people who support you.

- Our biological family is just one connection we have, but we also create our own “chosen family” of close relationships. You may feel compelled to send a card or write a note to someone you feel creates a paternal presence in your life like a good friend, mentor, or another relative.

- Allow yourself rest as you move through the day as grief can be an exhausting experience on our minds and bodies.

Maybe you’ve lost your father or father figure to death, or you’ve lost your father figuratively because of dementia, or you’ve lost your father in your life because of his unacceptance of your lifestyle. In whatever case, you’re not alone.

However you navigate this day, know this:

- If you feel happy, that is okay

- If you feel sad, that is okay

- If you feel angry, that is okay

- If you feel a roller coaster of emotions, that is okay

- If you feel nothing, that is okay

- If you don’t WANT to feel anything today, that is okay

The reality is that no one can tell you how to feel about your situation.

Your feelings are valid. However you choose to be, honour that, honour you.

Grief, Exhaustion, & Rest

Many people consider grief to be a response to the death of a loved one, but we grieve so much more than that. Grief is an emotional response to loss of any kind. Both real or perceived loss can trigger the response. The loss of a job, a miscarriage, a breakup, losing a sentimental item, or big life changes like moving can all cause grief.

Grief fatigue is a very real thing. Even though we know that grief is a healthy response to loss, it’s perfectly normal to get tired of it. You’re not in intense pain, but it also isn’t getting any easier yet. It’s exhausting. Grief exhaustion refers to the deep and pervasive fatigue often accompanying the grieving process. It goes beyond the typical tiredness we experience in our daily lives and stems from the immense emotional and psychological strain that grief places upon us.

Grief can leave you feeling drained, both physically and mentally, making even the simplest tasks seem overwhelming. Even typical activities can feel like too much when our physical body and brain refuses to cooperate. The mind and body are closely connected and the grief process is a good example of that. The mental and emotional toll of grief can wreak havoc on a person’s mental and physical well-being.

Emotions are not always easy to deal with and having intense ones can be incredibly draining. Grief is a complex emotion that can be mentally and physically taxing. The profound sadness and range of emotions experienced during the different stages of grief can lead to fatigue and exhaustion. Even though you’re tired, you may have trouble sleeping or sleep a lot and never feel rested.

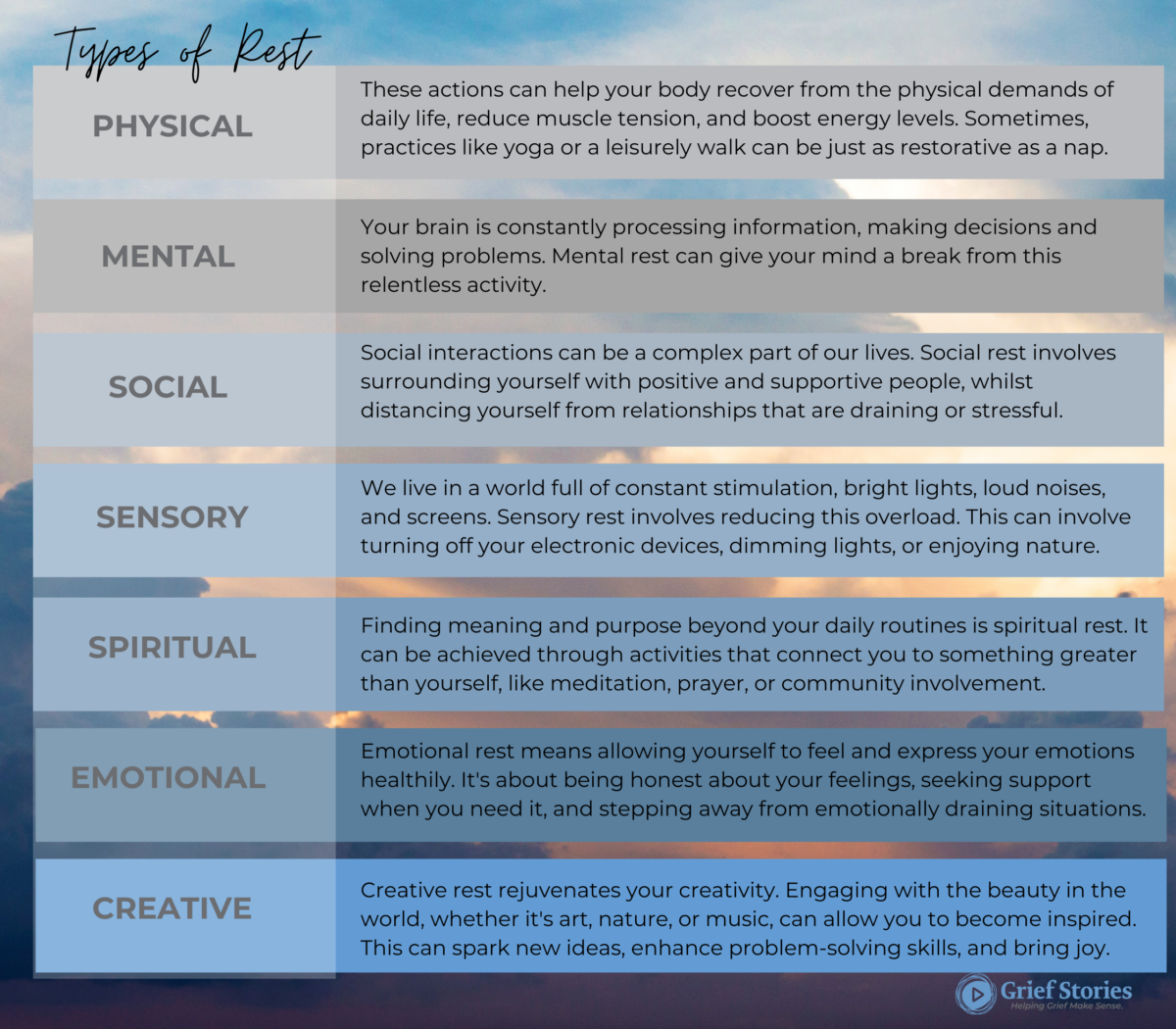

We often blame grief exhaustion on sleep deprivation—and that is a component. Sleep is essential, and needs to be prioritized. But, so many of us still feel exhausted and burnt out even when we finally start sleeping. Grief exhaustion isn’t solved with more sleep. Dr. Saundra Dalton Smith says we need seven types of rest. As I read her work, I find it especially applicable to grief.

Dr. Saundra pointed out that taking a comprehensive approach to rest is a bridge to better sleep and this is handled with attentive self-care. When we talk about rest outside of sleep, our minds might immediately jump to stereotypical “self-care” activities, like getting a massage or taking a bubble bath. Real self-care is nurturing our current needs. We might need to rest mentally, or to reconnect with our friends, or to be vulnerable with our emotions. Our needs are often rooted in the types of rest and what we’re lacking.

Being able to pinpoint what you and your body need in terms of rest will allow you to address the area and choose a restful activity that fits your needs.

When we understand the types of rest, we can become better aware of our own needs and make small changes in our lives that leave us feeling more whole, more energized, and more refreshed.

Grief Busting Zine [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. We’re sorry you’re feeling this way right now but so glad you’re reading this.

This zine is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

Physical copies of this sine were originally distributed at Cultivate Festival in 2023.

Community Grief Toolkit [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in the community. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and how to build the resources for further support.

What Can Help with Early Traumatic Grief?

By Claire Irwin

When your child dies you are thrown into a nightmare. None of this is expected to be easy.

Even after several months, it still isn’t. There have been some things that have helped us during

our grief. Maybe they will help you, too.

1. Let someone organize a meal train. The community rallied, making sure we had meals

delivered to our home for weeks after our daughter died. I have zero idea what we would have

done without this. Right after this traumatic loss I couldn’t even think about eating, let alone

cooking and meal planning.

2. Grief counselling. Our counsellor comes every week since the second day. Some may not agree, but honestly, we have learned some great survival tools and have our feelings validated.

To be able to talk about it all in a safe environment is very helpful, and just talking about

everything helps.

3. Find something to keep you busy. Mind you, we haven’t found our way to any gym yet or back to work, but we find other ways to move our bodies. Gardening, cutting grass, walks,

landscaping, anything really to get our bodies moving has really helped us.

4. Try journaling. I wish I started this earlier. If you can find it in you to do it, I recommend it. For me personally, it helps get whatever is in my head out on paper. I document how I’m feeling. I also get my anger out on paper too. I’ve been learning that you can let it build up inside of you. This energy needs to get out. I find writing very helpful for me. I journal daily. Plus, it helps me keep my days in order because they tend to blend.

5. Let your support system hold you. This has been a huge help. I don’t know where I would be today if I didn’t have the people closest to us. Lean into them and let them help. Use them as sounding boards. Whatever it is you need, if they are willing and able to be there for you, let

them. It’s not easy asking for help or accepting it, but it’s helped us feel loved and seen. It’s also

helped us back on our feet a bit.

At the core of it all, just remembering to breathe is sometimes all you can do. Something our

grief counsellor has taught us right from the very beginning:

Inhale 4 seconds…Hold 7 seconds…Exhale 8 seconds. Repeat as needed.

Like I said, surviving this grief and trauma isn’t easy, and it doesn’t come with a handbook. We

are all just doing the best we can, and it’s sucks all at the same time. Our loss cannot be fixed, it

can only be carried, and these are some of the things helping us to carry it now.

Shadowloss: loss in life

By Alyssa Warmland

Shadowloss is a term developed by Cole Imperi, a thanatologist and the founder of The American School of Thanatology. It describes the types of loss we feel in life, rather than the loss of life. Shadowlosses are things like divorce or the end of a long-term relationship, infertility, a medical diagnosis, losing a job, or the loss of some other relationship or thing. It’s a loss that impacts the life of an individual, as well as their social network in their life.

Sometimes, the loss of a being coexists with shadowloss. For example, when a loved one dies, families are often tasked with sorting through the person (or animal)’s belongings. When my dog died, I remember packing her bowls, her toys, her leash, and her collars away in a box I made space for in my crowded apartment because I couldn’t stand the loss of throwing them out. I remember holding her favourite toys and feeling deeply in grief. The “big loss” was my beloved dog, but the shadowloss was when I got rid of some of her belongings and how hard that piece was. It felt like a tug in the pit of my stomach when I turned towards the wall where her water dish used to sit, only to see an empty bit of wall.

Another example of shadowloss in my life was when I was fired from a job at a women’s shelter. I’d thought, all through my undergrad, that I would work in one. I worked hard to get my gender studies degree and to volunteer with feminist organizations that targeted violence against women. And, after applying four or five times, I finally got the job. I loved it, although the rest of the staff was far more conservative than I am and I sensed that I was not a great fit, in spite of my knowledge and my passion for the work. I was fired, just before the end of my probation, and refused an explanation as to exactly why. I was devastated. Not only was I losing a job, I felt as though I was losing a dream and a sense of self. Years, and a whole career, later, I still experience huge waves of grief related to that loss.

What we know about types of loss is that we experience grief related to them in very similar ways. Waves of sadness, anger, and the sense that something/someone is missing are a few things that can come up with “big loss” and with shadowloss. As with any type of grief, it’s not particularly useful to rank and compare types of loss or experiences of grief. But having language to describe the experience of grief associated with the loss of a thing or part of someone/their life can be useful. This allows us to acknowledge those losses as ones where we leave ourselves some space to grieve. It can also be another opportunity to connect in this life where there are shared human experiences like the complex plurality that is grief.

The Meaning of Tisha B’Av

By Richard Quodomine

Starting on sundown, July 26th, some Jews will begin to fast. Unlike the more well-known Yom Kippur, which is for atonement, Tisha B’Av is a specific holiday for mourning and grief. Its exact date varies with the ancient Jewish lunar Calendar, but is sometime in July or early August. All Jewish commemorations begin in the evening due to this lunar calendar.

Observant Jews will abstain from sexual relations, all forms of frivolity, wearing of leather, and work on this day. Just before the evening that begins the holiday, a “separation meal,” called seudah hamafseket,is eaten.It consists of bread and a hard-boiled egg dipped in ashes, accompanied by water. Talk about a meal to remind one of sadness. Once the evening of Tisha B’Av commences, one fasts for a full 24 hours. Please note that life and health are more important than fasting in Jewish tradition. If a doctor says a person should not fast, such as a woman who is pregnant, then fasting is forbidden.

Those of us of the Jewish faith also ascribe several sad events as having happened on the day of Tisha B’Av. For example, it is traditionally believed that both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem were destroyed on Tisha B’Av. In more recent history, the last Jews of Spain whom did not convert to Catholicism were said to have left Spain forever on Tisha B’Av. Spanish Judaism had been a critical component of the Islamic culture there and was part of its unique pluralism and beauty. Some of those events may not have happened “on that day” exactly. The point of the holiday is not to take dates literally, but rather to remind ourselves that grief is a life cycle event, and we all grieve at some time.

Further, there is grief over loss of life but also grief for losing ways of living, of culture, of beauty or perhaps our environment and our friends who are not well treated by society. Tisha B’Av is a Jewish holiday, but it is also a holiday that is universal. No, we shouldn’t all fast or refuse to wear leather. But we should recognize that mourning is important. Feeling loss and grief is a part of whom we are. In facing that loss and accepting that grief – along with emotions such as anger, sadness or resentment – we are able to process them. We’re able to find a part of ourselves. For example, when dealing with a person who has passed, the grief we bear is knowing that we must carry that which we have lost because the person who carried them with us can no longer do it. We must grieve, and then bring about again the joy that that person created. The prayer for the holiday concludes with the verse “Restore us to You, O Lord, that we may be restored! Renew our days as of old.” In accepting grief, we can be restored to joy.

Ripples of Grief: Supporting Ourselves, Others, and our Communities After a Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

When death knocks on the door of a community, each of us are impacted. Sometimes a death will touch many lives across a community, whether people knew the deceased personally or not. We may grieve the death of a family member, friend, or acquaintance, a well-known community member, or someone we are linked to by age, location, circumstances, etc. Community grief can feel overwhelming – we must tend to our own grief, but others in our life are grieving and hurting too. Each person in a community will grieve differently depending on their relationship to the person who has died, their own prior experiences of loss, and the unique coping strategies they rely on in grief.

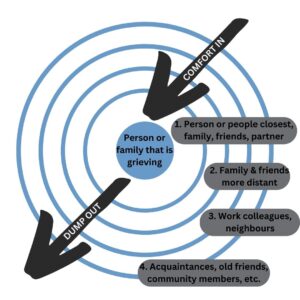

Developed by psychologist Susan Silk and Barry Goldman following Susan’s experience with a health crisis and her diagnosis with breast cancer, Ring Theory helps us learn how to support others and ourselves when a community death occurs.

Like a ripple on water when we drop a pebble into it, imagine a series of concentric circles. Those directly impacted by the crisis or death are in the innermost ring, with each outer ring consisting of those further removed from the crisis or death. Generally the immediate family, or those who lived with the deceased,are in the innermost ring, with close friends and other family in the next ring, co-workers and acquaintances in the next ring, and those in our greater community in the outer rings.

When someone experiences a death, those in outer rings pour comfort in, while those in inner rings are allowed to “dump” their thoughts or feelings out. When someone in an inner ring is dumping out their feelings, those in outer rings can show up with acceptance and care, listening and validating the person’s experiences.

Pouring comfort in can also be the offer of specific, practical help. This approach seeks the griever’s consent to accept specific support and comfort, it lets the griever say yes or no to the offer, and can confirm what kinds of support are most helpful to them. It’s important to offer support on the griever’s terms.

When a community faces loss, many who are impacted want to share their feelings about the loss. Susan recalled during her cancer treatment how some folks she did not have very close relationships with in her community would show up unannounced, forcing her to accept support, or people would talk about their own feelings about her diagnosis. Dumping feelings onto someone in an inner circle is not helpful. It can leave those experiencing the loss most personally as if their loss is unacknowledged. When we know which ring we sit in after a death, we can connect to our own outer rings anytime we need to tend to our feelings of grief. If we find ourselves thinking about reaching out for support from someone who is in an inner circle compared to our relationship to the deceased, we should take a step back. Is there someone else that may be located in the same ring as us, or someone in a ring outside of us that we can reach out to instead? Sometimes actually drawing out the rings of folks in our own life impacted by a death can clarify where we need to support others, and who we can connect with for our own support.

Whether supporting others, or seeking support ourselves, a helpful phrase may be “Would you like to be heard, helped, or hugged?” Being heard means receiving supportive listening and validation. Being helped may mean brainstorming and collaborative problem-solving, or providing specific practical help with tasks. Sometimes there are no words or help we can offer, but, if welcome, our steady presence and a comforting hug can communicate our support.

Each person in a community will be impacted differently by a community death. It’s important to remember this theory about who we need to pour comfort into, and who we ourselves can dump out to as we navigate a community loss.

Articles Reviewed for Blog Post:

https://karenwulfson.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/How-not-to-say-the-wrong-thing1.pdf

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-xpm-2013-apr-07-la-oe-0407-silk-ring-theory-20130407-story.html (actual article in LA Times first written by Susan Silk – first link is PDF version of same article)

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201705/ring-theory-helps-us-bring-comfort-in

The First Fathers’ Day Without Dad

By Richard D. Quodomine

When you lose a person in the generation before you, you begin to think about what they meant to you. When you lose a parent, you think about all they meant, and you hoped you either lived up to the best of yourself, or in some cases where the parenting was not as instructive or kind, you hope you’ve raised yourself beyond difficult circumstances. If you’re fortunate, Dad pushes every endeavor and delights in your successes and constructively scolds you when you fail without ever making you feel embarrassed or willfully stupid – unless of course, you were actually willfully stupid.

Did we have our differences? Absolutely. My father was more conservative than I am politically, though he rejected hateful politics and would not vote for it. We come from a mixed religious family, and my father was Christian, I am Jewish. We had philosophical differences and we approached life differently. But we also valued accomplishment, kindness for its own sake, and service in the public good. He is part of the reason I have chosen a career in civil service. I believe government can and should serve at the behest of its citizenry, and while he mistrusted government intrinsically, he had respect for my approach in working for it.

As part of my research in the public interest, I went to India for a conference. While en route, somewhere between Zurich and Delhi, my Dad suddenly passed from a cardiac arrest. I couldn’t return home for several days, so I soldiered on without telling anyone at the conference. I figured the way to honor his memory was to do my very best. He was gone – and weeping in my hotel room wasn’t what he would have wanted.

Dad had a heart condition, but he had had corrective surgery and was otherwise in outstanding physical shape for his age. He was my Mom’s primary caregiver. This was especially tragic because she has dementia. Sometimes, I get angry that Dad is gone because the burden is much greater on myself and my family. Sometimes, I am so grateful that he gave me the strength to help care for Mom. Most of the time, even months removed, I’m just missing talking to my Dad.

The first father’s day without Dad is the hardest, or so “they say.” I think that is true, but it’s harder not because I am sad, but because there’s nothing that can replace all that he was. It’s trite to say “he lives in me.” I think it’s better to say “I take what he has given me, and I will grow and make this life my own.” I don’t think anyone should strive to be “just like” their parent. They should strive to be their own authentic selves, using the best of their parent as the cornerstone, not the ceiling. In Judaism, we say “May their memory be for a blessing” as a condolence. Dad’s memory is, for certain, a blessing.

Mourning a Man I Never Knew

By David Newland

The following blog post is a reworking of a post originally written in 2005 under the same name on his website.

This spring, I turned fifty-four. I have now outlived the father I never knew: my biological father. It’s been almost twenty-three years since we spoke; eighteen years since I learned of his death. I’m still dealing with the strange grief of his loss.

As an adoptee, I always had questions about my origins that my loving, caring adoptive parents couldn’t answer. In my twenties, I applied to Child Services for more information, and after eight years of waiting on my part, they did a search in 2000. After some effort, they couldn’t find my birth-mother, but quickly produced contact info for my biological father. They offered to put us in touch.

After jumping through a few official hoops, we emailed back and forth a bit, and finally, we spoke on the phone, maybe three times in all.

I can’t even describe what that was like – intense, starkly honest, humorous and deep. Here was a man who had made most of the same mistakes I had, only far worse. Depression, drugs, divorce. Family problems. Anger management. Women. He hid nothing, as far as I could tell, although his stories sometimes conflicted.

I didn’t hold anything back either. I insisted that he honour my experience as an adoptee. It wasn’t easy for me, handling the big hole in my life. He had a hard time understanding that. He said his own kids had it a lot worse than me. He was right, but that wasn’t for him to say. I heard it from them.

It was good to connect, but I knew he wasn’t good for me. I chose not to pursue further connection. I knew he was out there. He knew where I was.

There was no contact for a few years. And then one day, in January of 2005, I found out he was dead. I was online at work, looking for some information on the original (Polish) spelling of his last name, and wham! the first thing that came up was a memorial page. He had died, nearly a year before, in March 2004, aged 54.

I never knew him in life. I still don’t know him in death. But I’ve been grieving him for a long time, in my way.

In 2016, still reckoning with the hole he left, I went to Red Deer to find his grave. I narrated that journey in a CBC radio documentary, The heartache and healing of finding my birth father. I never found a grave: only my own shadow over a four-by-four stake in the ground. I did enjoy a delicious steak sandwich at a local hotel restaurant he was fond of.

I’ve been back to Red Deer twice since then. The last time I went, even the stake was gone. And so was the steak sandwich, restaurant, hotel and all.

The picture on the memorial page linked above is the only likeness I ever saw of my birth-father. I always thought I saw my face in his. Now, having reached his age, I see his face in mine.

Reflections on Mother’s Day

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

The signs of spring start to show up: the bird calls, sleepy daffodils and tulips waking up from their slumber, the trees beginning to bud ready to shade us with their leaves all season. And then, the flood of Mother’s Day emails start crashing into our inboxes.

Mother’s day is a holiday where we show appreciation and care for the maternal roles in our lives. However, this holiday can feel very overwhelming for those of us who are grieving the death of a mother figure, a mother grieving their child, or those of us grieving the loss of not being able to become mothers ourselves. The ads, commercials, and displays at the store, designed to be appealing and inviting become a painful grief trigger as we go about our day, our minds and hearts going to the person we’re grieving who isn’t alive to receive their flowers or gifts. Feeling as if our grief is heightened on holidays or times of celebration is a natural reaction to have. Often around these times of the year we gather with our loved ones, and our special person’s absence feels amplified.

Over the years, my grief reactions around mother’s day continue to change. At first, it was like a black looming cloud and I would avoid anything to do with Mother’s Day. Over time, I still have had hard Mother’s Days but the day looks much different. I may write to my mother, choose to ignore the day and do things unrelated to Mother’s Day, make a comforting meal from my childhood, or participate in a memorial event on Mother’s Day. Regardless of what I choose to do, or not do on Mother’s Day I make sure to give myself the space and compassion to rest and recover – grief can be exhausting.

There is no right or wrong way to grieve, nor how to go through Mother’s Day. Our relationship as mothers and children is unique, so too will be our grief. The following ideas may be how you’d like to take time to honour the person you’re remembering and grieving on Mother’s Day:

-Unsubscribing from Mother’s Day emails (some companies have a special opt-out message for folks to unsubscribe from these types of emails)

– Ignoring Mother’s Day altogether and doing something that fills you up (it could be going to a movie your person may have never wanted to go to or taking a long hike)

– Creating an altar with photos, keepsakes, and favourite things of your person

– Lighting a candle in their honour

– Writing them a card, updating them on your life and reflecting on your relationship

– Creating a new tradition or ritual to replace Mother’s Day

– Packing your day with connection and activities with trusted others who support you in your grief

– Having a day of nothing: allowing yourself to do what your heart is telling you (a bath, a nap, a cry)

Sometimes our grief may feel heaviest in anticipation of Mother’s Day or on Mother’s Day itself. As we enter May and Mother’s Day approaches, I wish for you to be compassionate towards yourself and move through the day in the way that fits your heart and relationship best.