Posts by Alyssa Warmland

Quiet Hope: Healing as a Nurse, Mourning as a Mom

By: Yhaimar Barile

I’m a nurse. I’m a writer. And I’m a mom who lost her son.

Last year, shortly before his eighteenth birthday, my son Gabriel died unexpectedly. Everything changed after that. Life split into a clear “before” and “after.” The world around me kept moving, but mine stopped. Nothing looked or felt the same—not my family, not my work, not even myself.

Grief changes everything.

Nothing prepares you for the kind of loss that tears through every part of your life, including your work. I believed, like many others, that after a few weeks of grieving, I could go back to nursing. I thought life would find a new rhythm, even without my child. What I didn’t expect was how grief and trauma would reshape how I could (or couldn’t) show up for myself and for my patients. I wasn’t a nurse grieving a loss; I was a mother reckoning with the trauma of losing her son.

It soon became clear that returning to bedside nursing was impossible for me in that season. That realization marked the beginning of a profound and seemingly permanent shift in my path and identity. Nursing was my calling, but now I am rethinking how I can care for others, contribute, and find purpose despite losing my son.

Grief reshapes you. I was still a nurse—but I was also a mother in mourning, learning to survive something that felt impossible. Healing started there. It didn’t come from answers or quick fixes but from learning to treat myself with kindness.

Healing is being gentle with where I am.

Healing starts with gentleness. It means meeting myself right where I am, day by day. Healing from trauma and grief means knowing what my mind, body, and spirit need. Some days, that means moving my body or nourishing myself as best I can. Other days, it means resting or letting creativity speak through writing or art.

Healing is work, but not the hustle kind. It’s being intentional in caring for myself, trying when I can, and not judging myself when I can’t. Honoring even the smallest act of self-compassion is essential. This is how I rebuild, one gentle step at a time. In these small steps, I find the quiet strength of hope.

Hope is the act of showing up.

Hope, for me, doesn’t arrive with fanfare. It’s often quiet—the choice to keep showing up for myself and my family, despite my imperfections. Right now, hope means reaching for a new purpose: health content writing, connecting with those who understand loss, or honoring Gabe’s memory in ways that feel true.

Most days, hope means allowing the possibility of meaning to return, even in small moments. It’s trusting that my life and work can grow and change, and that honoring my grief is compatible with helping others.

If you’re walking through the trauma of grief, please know healing may feel like work, because it is. But it’s work that starts with gentleness and self-compassion. Hope doesn’t have to be grand. Sometimes, it’s simply the act of showing up. That is enough. You are not alone.

About Yhaimar Barile:

I’m Yhaimar Barile (she/her), a nurse, writer, wife, and mother learning how to live after the loss of my son Gabriel, who died unexpectedly just before his eighteenth birthday.

I’m Yhaimar Barile (she/her), a nurse, writer, wife, and mother learning how to live after the loss of my son Gabriel, who died unexpectedly just before his eighteenth birthday.

Born in Venezuela and now living in Atlanta, I run Legacy Nurse Writer—a name that carries Gabe’s spirit and my hope to keep helping others in his memory. Grief changed everything, including how I care for others, how I work, and how I move through the world.

I’m raising my son David alongside three incredible stepboys. Most weekends, I’m at the soccer field, cheering on with quiet pride. Our Boston terrier, Luna, is always nearby, sensing when I need a nudge, or a reason to smile.

Lately, I’ve found comfort in glass fusing—turning broken pieces into something whole and beautiful. It’s become a kind of language for everything I can’t quite say.

What gets me through? Gentleness. Storytelling. Connection. I believe healing doesn’t mean moving on. It means carrying love with us and finding meaning in the process. Some days, just showing up is enough. And on the hardest days, I remind myself: even quiet hope counts.

Weaving the Tapestry of Love

Learning to become a better person is a wonderful consequence of being in a loving relationship with someone; you’re present in ways that help them grow into their best self. It’s an organic process you flow with on a journey we map out with intention, though in reality, it remains unknowable.

That is why a deeply loving relationship is like weaving a beautiful tapestry. You start with a blank canvas. With every experience a new thread is added—each a different color. The layers of time continue this process, including the good and troublesome of what life has to offer. The richness of color intensifies, fleshed out over the crucible of a relationship. In the end, if the kindness and beauty of love have been yours to share, you’ve woven a work of art.

My Uncle Sam had this type of relationship with his wife, Syl. Sam was remarkable for his easy-going nature. Syl, aka, “the little general,” was not even 5 feet tall, but formidable in demeanor. Sam and Syl had a long, happy marriage of 68 years.

When my uncle was 88, he began to develop some neurological symptoms. Medicine wasn’t working, so surgery was the next option. The day before surgery I was at the hospital. Sam was in good spirits; his usual affable self. I was in the room with just Syl and him. We talked about the upcoming surgery and then the conversation shifted: He said to Syl, “You know I love you” and remarked how beautiful she was. She laughed and rolled her eyes. Syl was being her usual self—a tough nut to crack. Sam was undeterred. He said he loved her now more than ever.

Sam continued to passionately express how much Syl meant to him. Syl smiled and her demeanor softened. I was so riveted by what my uncle was saying that I couldn’t tear myself away, even though it was such a personal moment between them. It was his love letter to her, and he was emphatic in wanting her to know.

After this intimate exchange, I immediately told my cousins about the amazing conversation between their parents. I was so grateful to have been present to bear witness and share the story. Sam spent the rest of the day alert and kibitzing with his family. When he came out of surgery the next day, he was in a coma and never regained consciousness. Sam died a month later. The words he uttered to his wife and family the day before his surgery were the last he ever spoke. Sometimes those who don’t have much time provide great gifts to the rest of us. Sam placed the final stroke on his masterpiece.

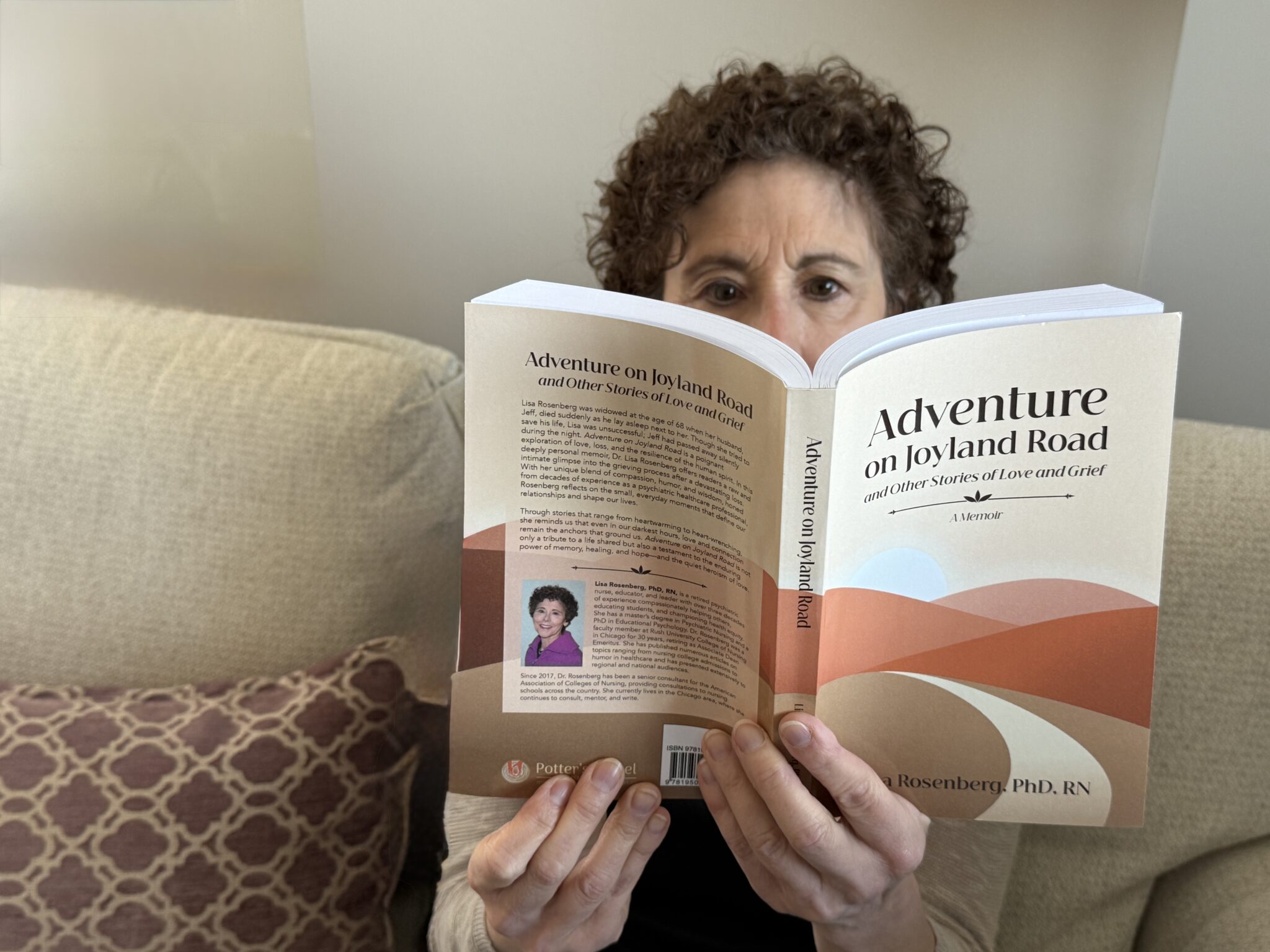

By Dr. Lisa Rosenberg

Dr. Lisa Rosenberg is a psychiatric healthcare professional, writer, and widow who never expected to navigate grief so intimately. When her husband, Jeff, died suddenly beside her in the night, she found herself confronting profound loss, love, and resilience—all of which she captures in her memoir, Adventure on Joyland Road and Other Stories of Love and Grief. With a career dedicated to understanding the human mind, Dr. Rosenberg blends deep psychological insight with personal storytelling to explore the lived experience of grief. Her writing is honest, humorous, and deeply compassionate, offering guidance to anyone who has lost someone they profoundly loved.

With a master’s in Psychiatric Nursing and a PhD in Educational Psychology, Dr. Rosenberg spent 30 years as a professor at Rush University College of Nursing in Chicago, retiring as Associate Dean Emeritus. Her career includes pioneering articles on humor in healthcare, extensive presentations, and, since 2017, senior consulting for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Based in the Chicago area, she writes, mentors, and consults, offering compassionate wisdom to those navigating grief.

You Can’t Always Get What You Want

“Happiness is a choice.” A friend of mine posted this quote on Facebook the other day. She then asked others what that quote meant to them. The responses were interesting and expected, and some were even inspiring. It’s so easy to say “I choose to be happy” when life is going well. On the other hand, when life has dealt you extremely difficult circumstances, like the loss of both of your parents and your spouse in a year, suddenly the choice requires a lot more effort.

I’m not saying it can’t be done. Some days I just really have to work at it. One of the things that made me the happiest in this world was my husband. I was madly in love with my Joe for all the days before he died, and I still am today. That is not a choice. It’s ingrained in me. His death didn’t lessen that love.

So, when someone says to me that I should “choose to be happy”, I hope they understand that it’s so much easier said than done. Choosing to be happy means choosing to enjoy this life without Joe. Enjoying this life without him means learning how to not feel guilty about that enjoyment. Not feeling guilty means choosing to let go. Even though I am still madly in love with my late husband, I am no longer married to him. Accepting that fact makes me sad.

Choosing to be happy is so hard when you are sad.

My friend was just asking for opinions, and in no way was her question directed at me. It just stirred up a lot of thoughts in my mind. The Rolling Stones were right, “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you just might find you get what you need.”

More than once in the last year someone has suggested that I should “choose to be happy”. If they read this, I hope they understand what it takes for a grieving person to do just that. And I hope they know that I am trying to find happiness amid the heartbreak every single day.

Suicide Loss Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDF]

Approximately 4500 people in Canada die by suicide each year. That is approximately 12 people who die by suicide each day. In 2022, 49,476 Americans died by suicide. That’s 1 death every 11 minutes. On average, 5 people grieve for every death. That leaves over 250,000 people experiencing suicide-related grief and distress. Grief Stories has seen these impacts firsthand: suicide loss has been the most viewed topic on our Youtube channel all year. At Grief Stories, we passionately believe sharing stories and insights fosters connection, helping people cope with grief. Grief Stories is proud to announce the release of our latest toolkit titled: the Suicide Loss Toolkit.

Our suicide loss toolkit pulls together our original multi-media resources about grief into an easy-to-access format which provides helpful information about the grief experience, stories of suicide loss from survivors, and helpful strategies to move through grief. This toolkit has been curated by mental health professionals for other helpers, for individuals, and their networks as they navigate grief and loss together. They are free to download and use.

You can download the toolkit here.

What is a Toolkit?

Grief Stories strives to create a free, accessible, diverse, inclusive, on-demand resource, reducing barriers to accurate online information about grief, helping grievers and those who support them using innovative technology. Our toolkits curate our multimedia content into an easy-to-navigate format on different topics, all vetted by healthcare professionals with expertise in grief and loss.

Toolkits are a popular knowledge translation strategy for disseminating health and wellness information, to build awareness, inform, and change public and healthcare provider behaviour. By keeping our content and toolkits free to access, we help individuals feel confident in connecting with and supporting grievers in their life, while at the same time providing accurate information about grief to help grievers make sense of their experience, one story at a time so they feel less alone.

As a virtual organization, we envision a world connected and supported in grief through our free multimedia library of content. Grief Stories relies on donations to cover many operational costs, including content creation. Each donation we receive allows us to share even more stories, helping grief make sense. If you, or someone in your life has found one of the toolkits helpful, please consider making a suggested donation of $10.00.

For less than the price of a premium streaming service, you can help us share our stories even further with those who need them most – helping grief make sense, one story at a time.

Infant & Reproductive Loss Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDFs for Individuals and Professionals]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. Mental health professionals designed this toolkit for individuals, parents, caregivers, and families navigating perinatal and reproductive loss.

Reactions to pregnancy and reproductive loss are as unique as fingerprints. Some can process the experience relatively quickly, while others experience unrelenting pain and grief.

We hope that this toolkit can be used to add tools to your toolbox and offer words of support, guidance, and care as you navigate life after loss.

Download the Infant and Reproductive Loss Toolkit for Individuals HERE.

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit was designed by mental health professionals for other professionals who support individuals during their reproductive years and beyond.

It contains information about grief and navigating the impact of loss alongside your clients.High-quality grief care includes compassionate and open communication, informed choice and individualized care. Compassionate communication, the most important element, is required in all aspects of care throughout and following loss.

Download the Infant and Reproductive Loss Toolkit for Supporting Professionals HERE.

What is a Toolkit?

Grief Stories strives to create a free, accessible, diverse, inclusive, on-demand resource, reducing barriers to accurate online information about grief, helping grievers and those who support them using innovative technology. Our toolkits curate our multimedia content into an easy-to-navigate format on different topics, all vetted by healthcare professionals with expertise in grief and loss.

Toolkits are a popular knowledge translation strategy for disseminating health and wellness information, to build awareness, inform, and change public and healthcare provider behaviour. By keeping our content and toolkits free to access, we help individuals feel confident in connecting with and supporting grievers in their life, while at the same time providing accurate information about grief to help grievers make sense of their experience, one story at a time so they feel less alone.

As a virtual organization, we envision a world connected and supported in grief through our free multimedia library of content. Grief Stories relies on donations to cover many operational costs, including content creation. Each donation we receive allows us to share even more stories, helping grief make sense. If you, or someone in your life has found one of the toolkits helpful, please consider making a suggested donation of $10.00.

For less than the price of a premium streaming service, you can help us share our stories even further with those who need them most – helping grief make sense, one story at a time.

Grief, Breastfeeding, and Care

In this essay, I share a bit about my story of grief and breastfeeding. I also share some thoughts about the cultural grief some people are carrying about the lack of support afforded to lactating families whose goal it is to feed their baby from their body. I use some gendered language throughout this essay (ie. breastfeeding, mother/mom, etc.) because it is the language I use to describe myself and my experience. There are other great gender-neutral terms out there, some of which I have incorporated into this essay.

Read More

Grief & Drug Poisoning Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDF]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in communities of people who use drugs and friends, family, and professionals who work with people who use drugs. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and to build the resources for further support.

Download for FREE here.

What is a Toolkit?

Grief Stories strives to create a free, accessible, diverse, inclusive, on-demand resource, reducing barriers to accurate online information about grief, helping grievers and those who support them using innovative technology. Our toolkits curate our multimedia content into an easy-to-navigate format on different topics, all vetted by healthcare professionals with expertise in grief and loss.

Toolkits are a popular knowledge translation strategy for disseminating health and wellness information, to build awareness, inform, and change public and healthcare provider behaviour. By keeping our content and toolkits free to access, we help individuals feel confident in connecting with and supporting grievers in their life, while at the same time providing accurate information about grief to help grievers make sense of their experience, one story at a time so they feel less alone.

As a virtual organization, we envision a world connected and supported in grief through our free multimedia library of content. Grief Stories relies on donations to cover many operational costs, including content creation. Each donation we receive allows us to share even more stories, helping grief make sense. If you, or someone in your life has found one of the toolkits helpful, please consider making a suggested donation of $10.00.

For less than the price of a premium streaming service, you can help us share our stories even further with those who need them most – helping grief make sense, one story at a time.

Creativity Helped Me Cope as a Child

Michele King is an End-of-Life Doula and Expressive Arts Grief Support facilitator. She companions people through serious illness and at end of life with a passion for normalizing conversations around death and dying.

I can still vaguely remember the day like a fuzzy picture in my mind. I was playing on our front lawn with the neighborhood kids. My friend’s mom came running up the driveway. I could tell something was wrong as she had a serious look on her face. She said we needed to go into the house and pack up some things as we had to go to go to our grandparents. It was July 1976, and little did I know my dad had just died as a result of injuries from a motor vehicle accident. I was nine years old and my brother two years younger.

The next memory I have is laying on a mattress on the floor in my grandparent’s basement with my mom and my brother. It was morning and my mother announced she had something to tell us. I can’t even imagine how hard it must have been for her to tell us our father was never coming home again.

Right after she told us my dad had died, she also told us we had had an older brother that died when I was one and my younger brother had not been born yet. This turned out to be a huge revelation in my life decades later.

I was devastated at the loss of my father. He was my rock, my everything. Although he was away working all the time, he was the parent I had a secure attachment to. My relationship with my mother was complicated then and throughout my life. Later in life I learned that when my older brother had died from a tragic accident and my mother’s depression affected me at a very crucial stage of my development. Her neglect of me resulted in an insecure attachment and we always struggled in our relationship.

To process my grief and make sense of my deep feelings of loss and grief I connected deeply to creativity. At that time, I don’t think people thought children really grieved over death, and there was still a strong stigma attached to seeing a therapist. I was very fortunate to have two grandmothers who were also very creative that taught me to knit, crochet and sew. I sketched cartoon figures from magazines that I still have to this day. I gravitated toward anything that involved creative expression. Only very recently, with scientific studies being done around trauma, toxic stress and creativity, has it come to light that as a child with few resources for expressing and processing grief, that being able to color, draw and create can help heal. Through creativity I was able to cope and process my emotions around my loss. Creativity saved my life as a child and I share it so others may find healing, too.

Getting Comfortable Talking About Grief

Post by Maureen Pollard, MSW, RSW

Getting Comfortable Talking About Grief

There was a time when death was part of everyday life. People didn’t tend to live long, and there was often a great deal of suffering while they were alive. Birth happened in the home, and death often happened there, too. If death happened elsewhere, the body was returned to the home whenever possible, for tender care and burial. Family members, and sometimes a trusted member of the community whose role it was to help, took care of the business of death.

We’re a long way from that now and in many cases death is turned over to the authorities. Medical diagnosis and treatment is often involved. We talk about battles, and fight to prolong life as much as possible. Death may be seen as a failure in our medical system; the enemy. This approach can sometimes create the illusion that we can defy death, when in reality death is inevitable for each and every one of us.

Since death can’t be avoided, it benefits us all to learn to talk about dying and death and grief. We need language for this universal experience. We need permission to ask our questions and share our stories. We need to know that what we are living through as our loved one dies, and in the aftermath, is a natural response to the loss we feel. We can get comfortable talking about it.

Be gentle. When you ask someone how they are, be mindful that they may not doing well, even if they seem to be managing. Try to use sensitive language and a softened tone when you check in with them.

Be kind. Let them know you are thinking about them and you’re available if they need support. Ask if you can help with specific tasks such as picking up some groceries or doing some yard work.

Be open. Share stories about their loved one’s greatest traits, or your best memories of them. Say their loved one’s name.

Be willing to listen. Let them tell you the parts of the story of death they feel comfortable sharing. If there’s something you can’t handle, offer to help them find someone who can be there for them as they talk about that part. Invite them to share stories about their loved one. Be prepared that they may repeat themselves as they try to adjust to the reality of the loss and hold on to their memories.

Be honest. If you don’t know what to say, tell them. They would likely rather hear that than have you stumble through platitudes that might dismiss their grief or hurt their feelings.

Be comfortable with silence. Once you say you’re sorry for their loss, it’s just fine to be quiet with them. You don’t need to fill the space with words or try to coax them to talk. Your presence is sometimes enough.

Everyone will experience death eventually, and being able to talk about it helps normalize this universal experience.

When Your Friend Has a Miscarriage

When Your Friend Has a Miscarriage

Alyssa Warmland is a content artist whose work focuses on fumbling towards an ethic of care and empowering people to share their stories in a way that keeps them well.

When my partner and I decided we were ready to have a baby, we thought it would be easy. Turns out, we were wrong. After six months of hoping, our first pregnancy was a chemical pregnancy. Two months later, I was pregnant again. When an ultrasound at 7 weeks showed no heartbeat, the loss was drawn out and difficult, requiring multiple interventions. I got pregnant again a few months later, and lost that one too.

We wanted to be open with people close to us, since these losses were huge in our life. When we told people, we found that most women we knew had their own miscarriage stories, and we found that, like with any loss, people rarely know what to say.

There’s nothing that can be said to change the fact that someone you care about has experienced a loss. Still, here are some ideas about what can help after a miscarriage:

1. I’m sorry you’re going through this.

As someone who has experienced several significant deaths, I feel pretty confident saying that this is a solid way to respond in any situation where someone is grieving for any kind of loss. It’s appropriate to acknowledge that they’re going through something.

2. Do you want to talk about it?

If you’re fairly close with this person, it’s worth asking if they want to talk about it. Be sure you have the emotional capacity and physical time to take that on. If you don’t have that emotional capacity or physical time, just don’t offer. Some people don’t process grief by talking about it, or they may just not want to in a particular moment. By asking, you’ve given them the option, letting them know you will hold space to talk about it if they wish.

3. Do you want some company? I’m available at [time, days].

This is another way of identifying a way you feel capable of being supportive. It can be lonely when you’re grieving and it helps to have people around physically. Sometimes it’s nice to have a distraction and talk about completely unrelated things. Miscarriage can be an intense experience, both physically and emotionally, at times, but it’s important to consider that even grieving people are whole humans and their grief isn’t all that’s going on for them.

4. I get that you’re going through a lot right now. Take whatever time you need.

It can be helpful to know that people realize you need a little gentleness or time or space or care. We live in a society where we put a lot of pressure on women to carry on with their lives during their pregnancy, especially early pregnancy, which people are typically expected to hide. It can be pretty challenging to carry on with everything in your life when you’re exhausted and nauseous. Miscarriage can be painful, physically and emotionally.

5. What kind of soup do you like?

Bringing people food is rarely a bad idea, especially if they’re sad or not feeling well. Soup is warm, comforting, and most people like at least one kind. Be a friend. Bring soup.

Grief and Secondary Loss

Post by Maureen Pollard, MSW, RSW

Grief and Secondary Loss

Secondary losses are those that often accompany the death of a loved one and may go unacknowledged beside the more recognized experience of that primary loss. Secondary loss includes such things as role, family structure, support systems, identity, faith, purpose and security. These connections are related to the relationship between the griever and the deceased, and will be different for every griever.

Secondary losses are complicated because they vary so much, and because they are often unspoken. It can be difficult to understand and accept these losses as they are often intangible. People are less likely to acknowledge that the griever might feel pain because of a loss of confidence related to the death of their loved one. We tend to see these issues as challenges to navigate rather than as losses worthy of grieving.

What can help?

Identify these losses. Recognize the many intangible ways that the death of an important loved one changes your life. When we acknowledge these losses it helps us understand why we’re feeling such deep pain and finding it hard to heal.

Seek validation. If your family and friends can’t accept that these losses are just as real and have a significant impact on your grief, look for other avenues of validation. Talk to a grief counsellor, or find a grief support group or an on-line forum where your thoughts and feelings about your secondary losses can be understood and accepted.

Take time to grieve these losses, too. You’re expected to grieve the absence of the person who died. Give yourself permission to feel this grief, too. Create rituals to honour the changes in your life and how they are impacted by and impacting your grief process.

Trust yourself to carry on. You can carry the grief you feel. In time, as you adapt to this reality, it will shift and you will feel ready to develop new strategies, roles and identities. You will create support systems that meet your needs as you are now. You will find a way to rebuild your confidence and re-establish security in your life.

Grief is all encompassing. Understanding secondary losses opens a door to a deeper appreciation of the complex layers of grief that we experience when someone we love dies. Although it can be a challenge to identify these intangible losses, the time we take to consider them may help us understand the ways that grief touches us in so many personal ways and that can help us have patience with your unique path to healing after loss.

Forgiveness at the End of a Life

Post by Maureen Pollard, MSW, RSW

Forgiveness at the End of a Life

One of the most difficult things about death can be the experience of unresolved conflict. When we’ve had a turbulent relationship with the person we are grieving for, it can really complicate our feelings. Forgiveness is a good goal, but it can be hard to navigate.

When a Person is Dying

It may be that a person who has been diagnosed with a terminal illness and is moving toward the end of life wants to tend to unfinished business. They may feel remorse, or have a strong desire to make amends and set things right. If this is the case, it may be that you welcome their overtures and feel ready to forgive them.

If you don’t feel ready, you are not obligated to forgive. Some damage is deep, with far-reaching consequences. Your healing will not necessarily happen on a timeline that works with the time that is left to the dying person who seeks forgiveness.

Alternately, it may be that you want to forgive their actions and look for opportunities to mend the rifts but they continue whatever attitude and behaviour caused the wounds you feel. It’s important to know that some people do not seek to redeem themselves in response to impending death. That is not your fault and you can’t control it. You can still do the work of releasing yourself from the cycle that has harmed you.

When a Person has Died

When someone dies suddenly, there may be no opportunity for conversations or actions that might have happened to help heal emotional wounds in a relationship. You’re left with unsettled feelings that may include anger, guilt, regret and shame, with no way to address them directly with the person.

Finding Forgiveness

Anger is an acid that can do more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything on which it is poured.

Mark Twain

It may be helpful to remember that forgiveness is for you. It is a personal process of releasing the pain of past wrongs against you. Forgiveness can happen whether or not the other person shows regrets or tries to make up for past wrongs.

Acknowledge your pain.

Accept it as your response to the other person, and allow yourself to feel the wound.

Seek some understanding of their motivation. What led them to those hurtful attitudes and behaviours?

Consider the possibility that they were doing the best that they could, even if their best was not very good and may have caused you to feel quite hurt.

Release yourself from the pain.

Give yourself permission to forgive them.

When you are ready, forgiveness is a great gift that you give to yourself.