Posts Tagged ‘grieving’

Kristal – Grieving the Whole Person

Kristal – Grieving the Whole Person

Kristal discusses the importance of recognizing and grieving the entire person who was lost – not just who they were before they had been using drugs.

Kristal – Harm Reduction

Kristal – Harm Reduction

Kristal speaks to the importance of harm reduction and how it can save lives. She discusses how accessing harm reduction leads to the creation of connections with community support. It allows community outreach members to connect with community members and get to know them, and to know to look for them if they don’t see them when they usually do.

Kristal – Lack of Memorials During Pandemic

Kristal – Lack of Memorials During Pandemic

Kristal talks about how memorials can offer closure to people who are grieving, find a community, and share stories. With the absence of this during the pandemic, many people turned inward to grieve or isolated, which can create safety issues and have an impact on mental health. She speaks to how this leads to depression, physical pain, and it compounds upon itself.

A Million Other Things: Grieving a Drug Poisoning Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

A parent sits across from me, anxiously wringing their hands. They will be returning to work after the sudden death of their child. “What if they ask? Do I tell them that they died of an overdose?” Terror flashes across their face. “What if they judge me? My child? What if they think I’m a terrible parent?” We take a moment to reflect on their child and I ask them to tell me about them. They pause, but then I notice their hands aren’t as tense as they cross them over their shoulders. “They were so thoughtful and gave the best hugs. Their smile would light up any room.”

Sister, father, son, niece, best friend – some of these words might be how you would describe your loved one who has died of an overdose or drug poisoning. People Who Use Drugs (PWUD) are not defined by their substance use – they are a million other things to those who love and miss them dearly. Drug poisoning and overdose deaths are stigmatized in our society. The focus is on how the person died, not who they are. Society still holds onto old notions and beliefs about drugs which come with a value judgment about people who use drugs, which further contributes to stigma. Not everyone who uses drugs is an addict and not all drug use is inherently problematic. People who use drugs deserve dignity and respect when we are remembering and honouring those who have died by overdose or drug poisoning.

More stigma means less support for people using drugs and those that support them. Much work has been done and continues to be done to dispel myths and stigma about addiction, drug use, and those who use drugs. Addiction is an illness: something that someone lives with, not something that defines them. These same values and judgments society has about drug use aren’t attached to folks who die of other illnesses. Society tends to view drug use and those who use them as a black and white issue. However, those who love someone who uses drugs weave a rich, colourful tapestry made of stories, reminders, and feelings about their loved one.

In my years as a grief therapist, those left behind want to share a special moment or memory about their loved one with a trusted other. When one is grieving a drug-poisoning death, this trust and sacredness without judgment offers the freedom to sit in the entirety of their grief—the grief they felt when their loved one was alive and when they died. Taking the time to use a loved one’s name in conversation, and asking the griever to share something about their loved one is a powerful tool for us on our grief journey. By initiating these types of conversations, we let the griever know that if they wish to, they can talk about their loved one. Sharing our stories are some of the most powerful ways one finds connection and healing through grief. It helps us feel less alone in our grief by sharing about what makes our person special. Those we love and grieve aren’t just a person who uses drugs – they are so much more. May each of us continue to share stories about our loved ones and the many facets their lives hold.

*DISCLAIMER* The scenario described in the article is a general reflection upon themes the author has witnessed through their grief counselling work and does not represent a specific individual in order to protect the confidentiality of service users.

Nicole – Power of Speaking About Lost Ones

Nicole – Power of Speaking About Lost Ones

Nicole discusses the importance of sharing memories of those lost to drug poisoning and speaking their names.

Nicole – Pandemic’s Effect on Safe Spaces and Mental Health Access

Nicole – Pandemic’s Effect on Safe Spaces and Mental Health Access

Nicole discusses how the pandemic affected access to safe spaces and shelters for those living rough and living with addiction.

Nicole – Pandemic’s Effect on Grieving as a Community

Nicole – Pandemic’s Effect on Grieving as a Community

Nicole discusses the ways the pandemic has affected the way people grieve as a community.

Nicole – Pandemic Leads to Increase in Drug Poisoning

Nicole – Pandemic Leads to Increase in Drug Poisoning

Nicole discusses the increase in drug poisonings during the pandemic due to a number of factors.

Nicole – Grieving as a community

Nicole – Grieving as a community

Nicole discusses the power of grieving together as a community. Finding connection and trust.

Lyss – Losing My Mother

Lyss – Losing My Mother

Lyss discusses losing her mother and how her first thought was that her mother would never meet her kids Now being a mother herself brings back many memories of her.

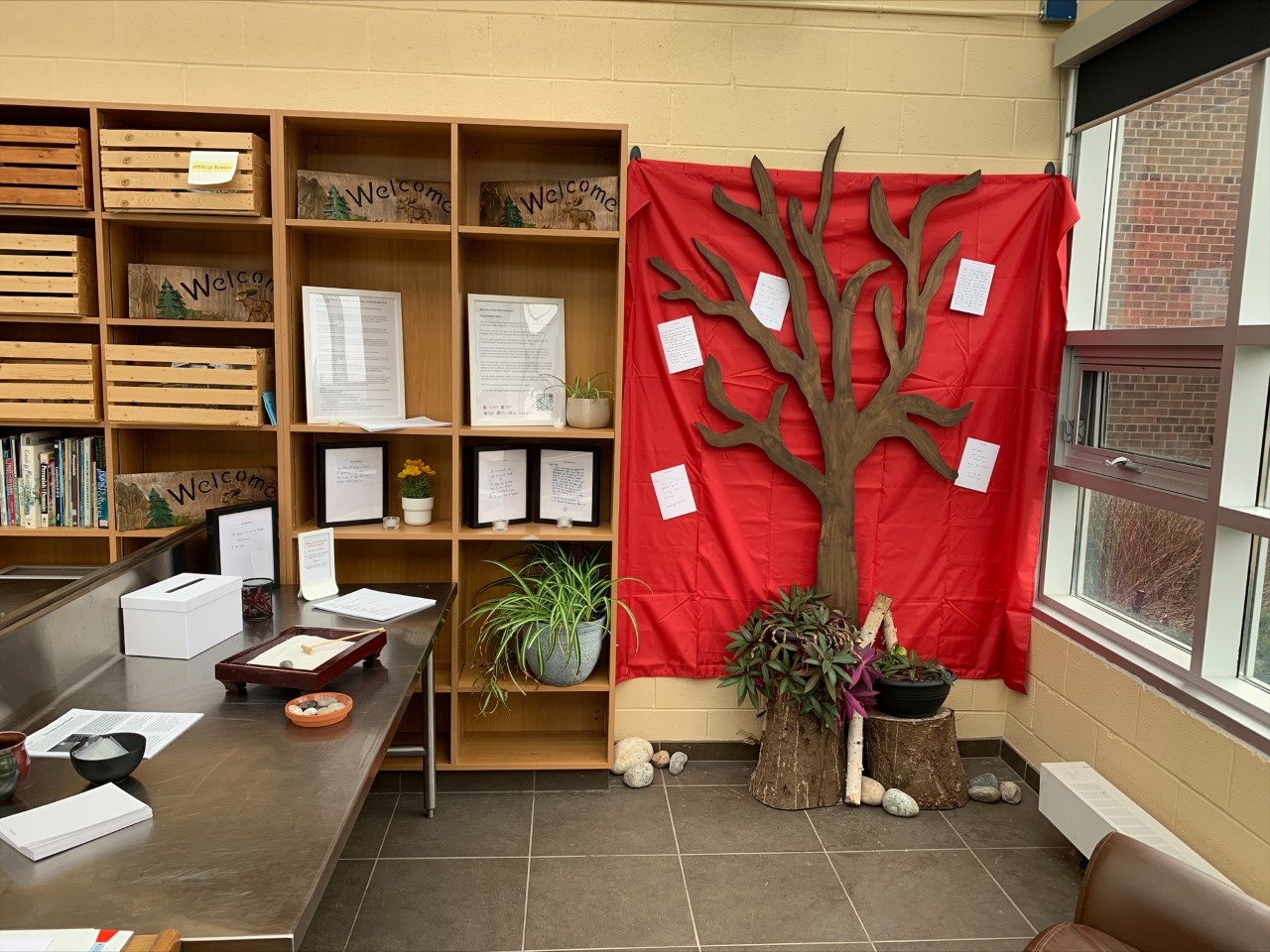

The Reflection Room® project: How storytelling supports processing grief

The Saint Elizabeth Foundation offers a project called the Reflection Room – a space for thinking and talking about dying, death, and grief.

The Reflection Room project is an evidence-based participatory art installation that was developed by researchers at the SE Research Centre and Memorial University in 2016. The project included a research component that evaluated the impact of Reflection Rooms as the project adapted over time to address changing needs.

The Reflection Room project was first developed to support people in community and healthcare settings to move from death-denying to death-discussing. From the first installation, the Reflection Room project has gone through three Phases of adaptation and continues to evolve.

Common elements across Reflection Rooms, whether they are set up to include an entire room, hallway, or corner of a room, include a quiet, calming space that invites visitors to read other people’s stories and post their own. The rooms are unstructured and unfacilitated, allowing visitors to engage with the space however they wish.

Over a five-year period from 2016-2020, the Reflection Room project was installed in 62 places across Canada, including in conferences, art galleries, hospices, and hospitals (Phases 1 and 2). Over a thousand stories were shared by individuals during their visits to these various Reflection Rooms. Results from the study from this period showed that storytelling can be an important part of grieving.

In 2020, Phase 3 of its adaptation and evaluation began with the SE Research Centre being asked to expand the reach of the Reflection Room to long-term care home communities in Ontario to respond to some of the accumulated pandemic-related grief in those communities. With the support of the Saint Elizabeth Foundation, Ontario Health Central, Family Councils Ontario, Ontario Centres for Learning, Research and Innovation in Long-Term Care, and Ontario Association of Residents’ Councils, over 50 homes signed up to host a Reflection Room®. In order to adapt to the environment of long-term care homes, an easy-to-set-up ‘kit’ incorporating instructions and materials (e.g., Reflection Cards, a red curtain to display Reflection Cards, candles, etc.) was developed and sent to homes free of cost. Overwhelmingly positive feedback has demonstrated that the Rooms support communities to work through grief by having a quiet space to rest and reflect, disclose emotions, process thoughts, and feel connected to others through sharing stories. The project often is complementary to other existing initiatives in long-term care homes such as palliative care committees and spiritual programs.

A collection of the stories shared over the course of the project is available to view on the Reflection Room website.

If you want to learn more about the project, contact foundation@sehc.com and listen to the Grief Stories podcast episode 64.

Neeliya Paripooranam, MSc, is a Project and Communications Manager at the SE Research Centre, overseeing the Reflection Room® project. Celina Carter, RN PhD, is a Senior Research Associate at the SE Research Centre. Paul Holyoke, PhD, is the Vice President, Research and Innovation at SE Health. Justine Giosa, PhD, is the Scientific Director, SE Research Centre and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Hana Irving, MA, is the Director, Philanthropic Programs for the Saint Elizabeth Foundation.

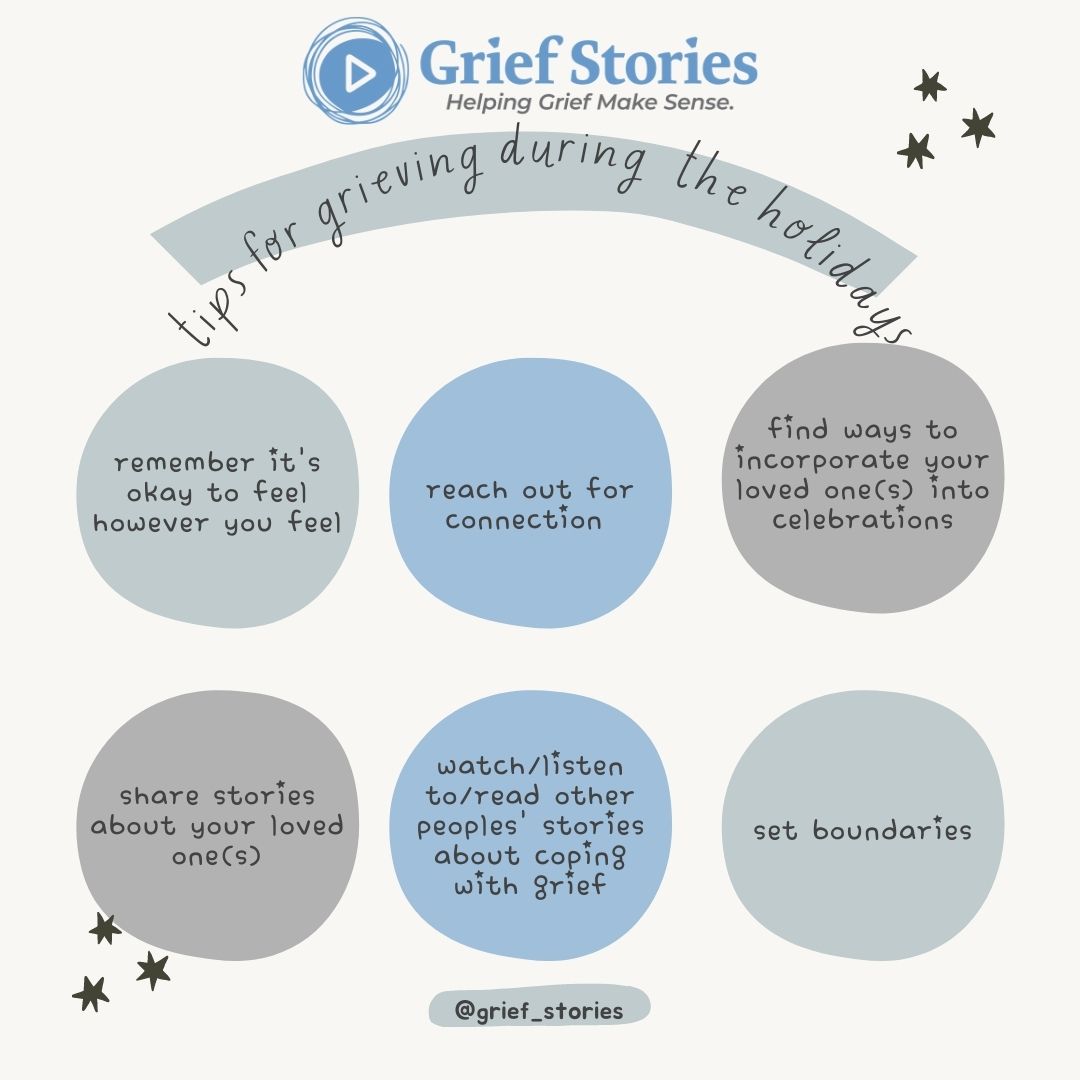

Tips for Grieving During the Holidays

By Alyssa Warmland

The holidays can bring up a lot of feelings, especially when you’re grieving the loss of a loved one. Whether it’s the first holiday season without someone, the holidays mark a time where someone you love died, or it’s just hard to be around celebration when you’re not feeling celebratory, December can feel heavy.

These are a few tips for grieving during the holidays:

Remind yourself that it’s okay to feel however you feel.

Feeling sad or mad? Feeling happy- and guilty for not feeling worse? Whatever comes up for you is normal. It’s okay to sit with your feelings, to give them some space when it feels right, and also to compartmentalize them if you feel like that’s best in the moment. You can acknowledge your feelings, put them in your pocket, and hold on to them during the family dinner if you want to. You can take them out of your pocket and spend time with them later. Grief is unique, and can show up in unexpected ways. It’s okay to feel however you feel.

Reach out for connection.

Sometimes we worry that we’ll make someone else upset if we mention our grief, or if we show up in a way that isn’t particularly festive. The truth is, the people who care about us want to hold space for us, even when we’re grieving. Connection can help us feel better.

Find ways to incorporate your loved one(s) into celebrations.

Did your dad have a favourite side dish your family always served at dinner? Did Oma make sugar cookies every year? Did your sister always compliment you when you wore red? Consider serving dad’s dish, or baking Oma’s cookies, or wearing red.

Share stories about your loved ones.

Sometimes it can be tempting to pretend the people we love haven’t died. As if, by not talking about them, we can pretend they’re still around. In fact, sharing stories about them can help honour them and to feel their presence. Remembering our loved ones out loud in connection with other people can feel healing.

Watch/listen/read other peoples’ stories and insights about grief.

At griefstories.org , we host stories and insights from people with lived experience in grief, as well as healthcare professionals’ insights on grief. These videos, podcasts, and blog posts are available for free 24/7, anywhere you can access the internet. Our hope is that this content may help you feel less alone.

Set boundaries.

Listen to how your body feels. You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do. You are safe and you are worthy of operating with integrity toward yourself. Grief can be hard, and it’s okay to be gentle with yourself as you move in and through it – even during the holidays. Set whatever boundaries feel right for you. There are no rules here. You’ve got this.